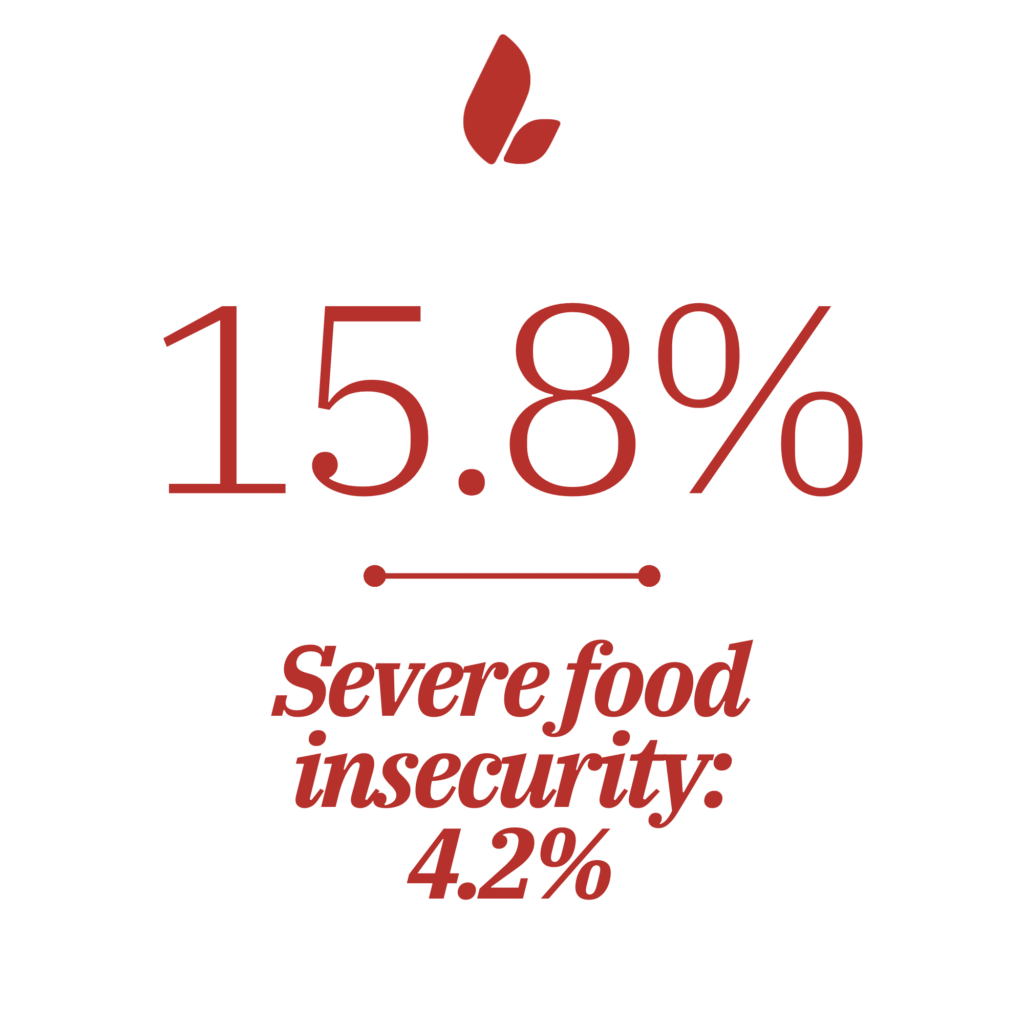

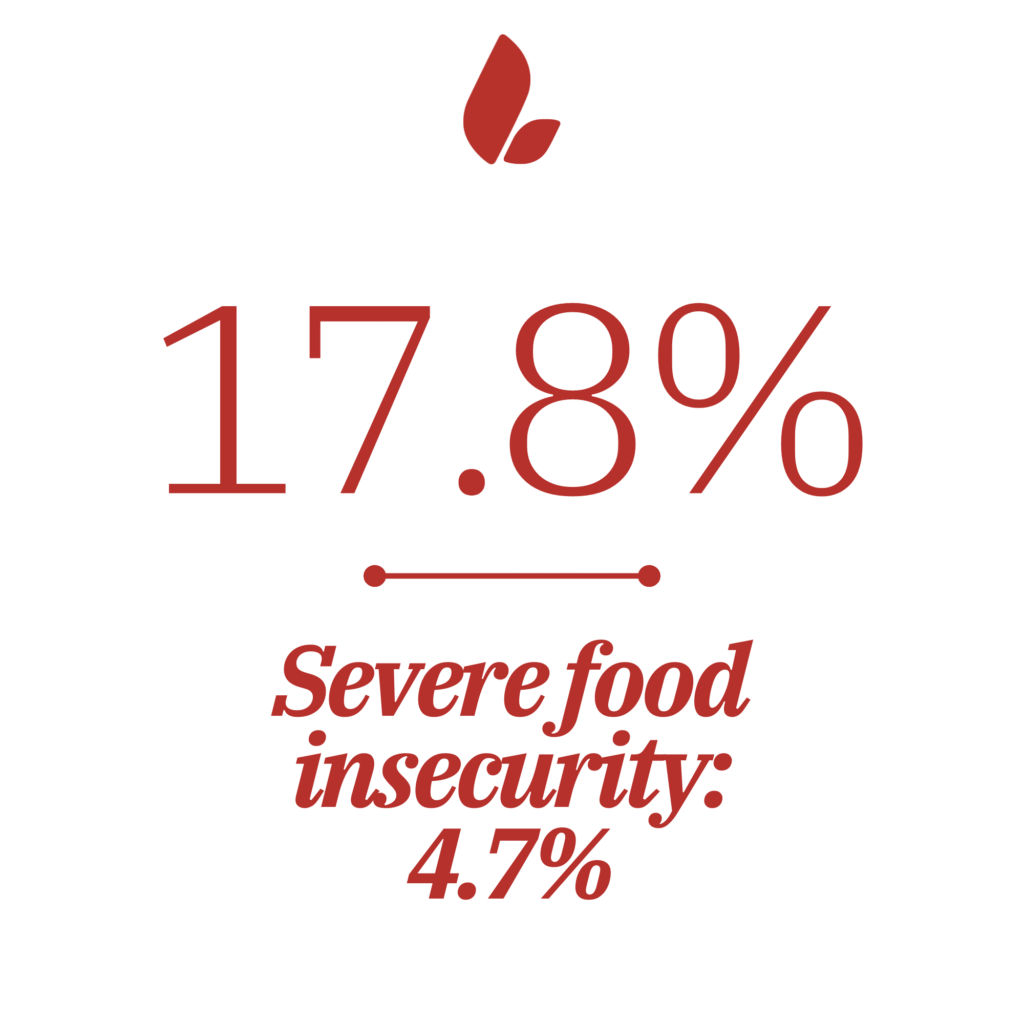

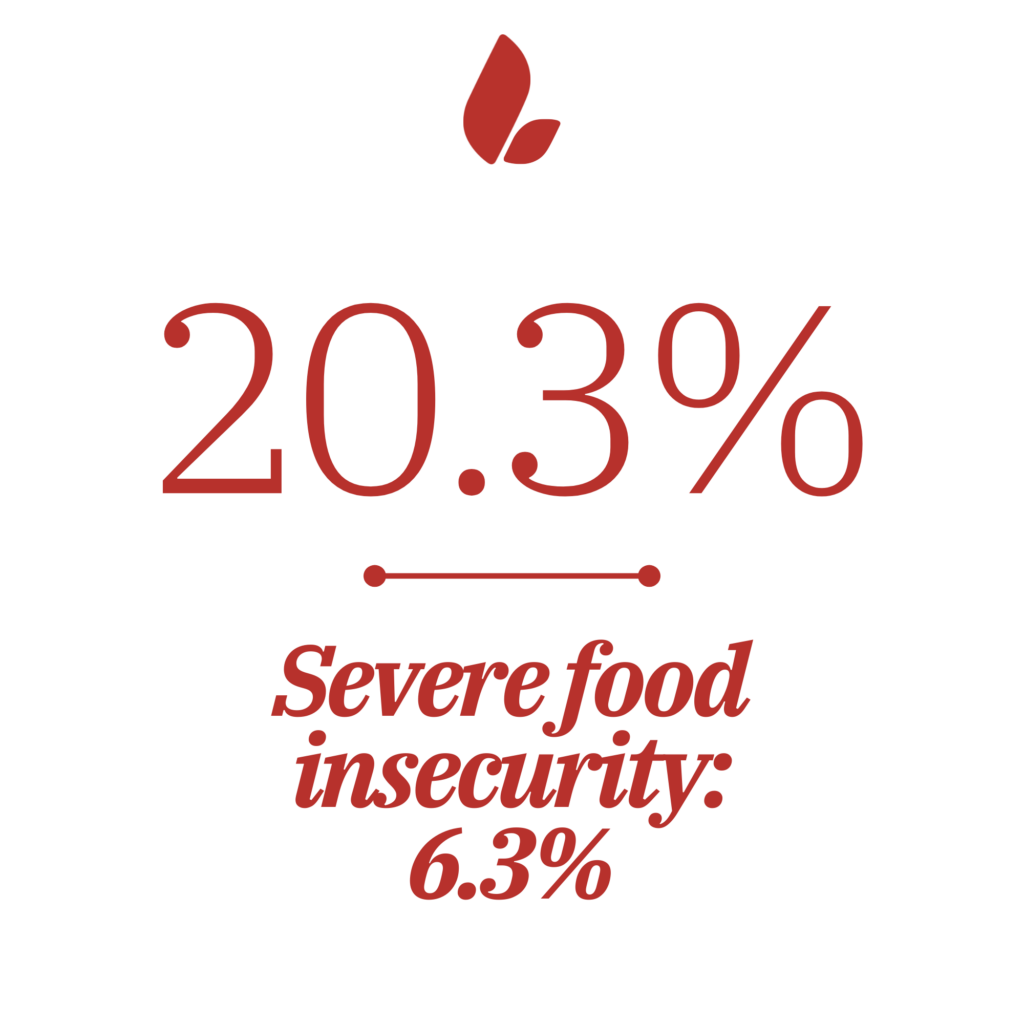

Let’s start by talking a bit about food insecurity, so we have it in the back of our minds as we learn more about food waste and food rescue. Here are the 2021 numbers for Canada overall, and Leftovers’ operating provinces, Manitoba and Alberta⁽¹⁾:

Canada

Manitoba

Alberta

What this translates out to in real-world terms is that 1 in 6 households in Canada and 1 in 5 in Alberta are food insecure, with Manitoba falling between the two. A recent survey done by Second Harvest⁽²⁾ suggests that the number of people accessing charitable food programs in Canada nearly doubled in 2022, and those same charities anticipate that number going to increase another 60% in 2023.

How many people is that?

With a population of 4.371 million in Alberta and 1.369 million in Manitoba (in 2019), that amounts to 1,130,995 people who experienced some form of food insecurity and 339,716 who were severely food insecure, meaning that they had gone one day or more without eating.

Food insecurity is not distributed equally. Whether or not your household is food insecure is deeply related to systemic racism and the ongoing impacts of colonialism. The most egregious example: 30.7% of members of Indigenous Nations in Canada who do not live on reserves are food insecure⁽¹⁾. That’s almost twice the national average.

The bottom line on food insecurity is that it’s not about food. It’s about income. Consistent government income supplements like Old Age Security and the Canada Child Benefit reliably reduce food insecurity. However, households accessing government supports like Alberta Income Supports or Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped are at increased risk of food insecurity, because these supports are dependent on political will, and because most provinces don’t index them to inflation, so as costs rise, the dollar amount of the support remains the same. (Exceptions are Quebec, New Brunswick, and Manitoba.)

Now, what about food waste?

Second Harvest worked with Value Chain Management International to do a fantastic report released in 2019 called The Avoidable Crisis of Food Waste, and here’s what they found:

Total food loss and waste (FLW) in Canada: 35.54 million tonnes or 58.1% of food inputs.

Avoidable, potentially edible: 11.17 million tonnes or 31.4% of total FLW⁽³⁾

Where is this avoidable, potentially edible waste happening? Almost half is at the production, processing, and manufacturing levels, another 21% is happening at the household level, and then the bit that food rescue focuses on–retail and HRI (hotels, restaurants, institutions) –accounts for a quarter of that potentially edible food waste⁽³⁾.

Let’s put this in context.

Here’s what’s happening in Alberta and Manitoba, according to Environment and Climate Change Canada⁽⁴⁾. We’re going to focus on the Industrial/Commercial/Institutional (ICI) sector here, because that’s roughly the equivalent of the retail and HRI categories mentioned above, where food rescue organizations can intervene to redirect good food.

Alberta/Manitoba solid waste composition:

Industrial/Commercial/Institutional: 34.3% is food (935,352 tonnes in 2016)

So here’s the math:

935,352 tonnes x 31.4% potentially edible

=

293,700 tonnes of food that people could have eaten got thrown out in Alberta and Manitoba in 2016

Remember how many people in Alberta and Manitoba were food insecure in 2021? More than 1,130,000 right? And almost 400,000 were severely food insecure. According to Good Seed Ventures⁽⁵⁾, the average North American eats 861.8 kg of food per year. So if all of that food had been rescued, it could potentially have fully fed 340,798 people. (Actually more, because North Americans, on average, eat more food per capita than people in any other part of the world.)

The three biggest categories of food that gets wasted are field crops, produce, and dairy/eggs. A lot of this happens during primary production and manufacturing, especially for field crops and produce, but these three are also the biggest sources of waste at the retail and consumer levels. Why does good food get wasted at the retail level? One reason is that it isn’t aesthetically appealing. We have an idea of what “good” food looks like, particularly when it comes to produce, and let’s face it, we don’t tend to go out of our way to buy a wrinkly pepper or a sprouting potato when there are other options available. Another problem is Best By or Sell Before dates. These have nothing to do with food safety, and only reflect the manufacturer’s best guess at when the product will no longer be at optimum quality. Unfortunately, especially when it comes to dairy, many people don’t understand what these dates actually mean, and will throw things out or refuse to buy things that are too close to the date, not realizing that the food itself is still safe and good to eat. Finally, vendors–like many bakeries–who respond to consumer demand with a production model of always-available, always-fresh, end up with a lot of unsold food at the end of the day, usually much more than can be sold as day-olds.

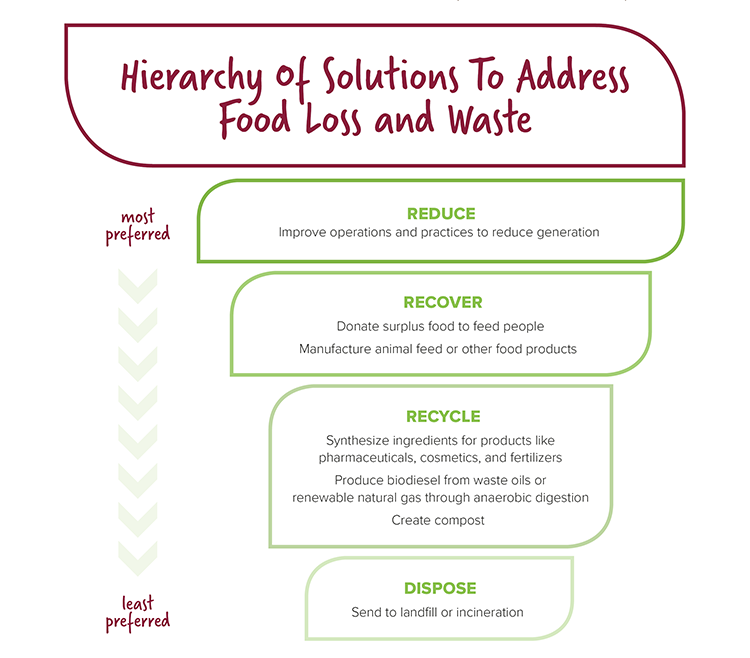

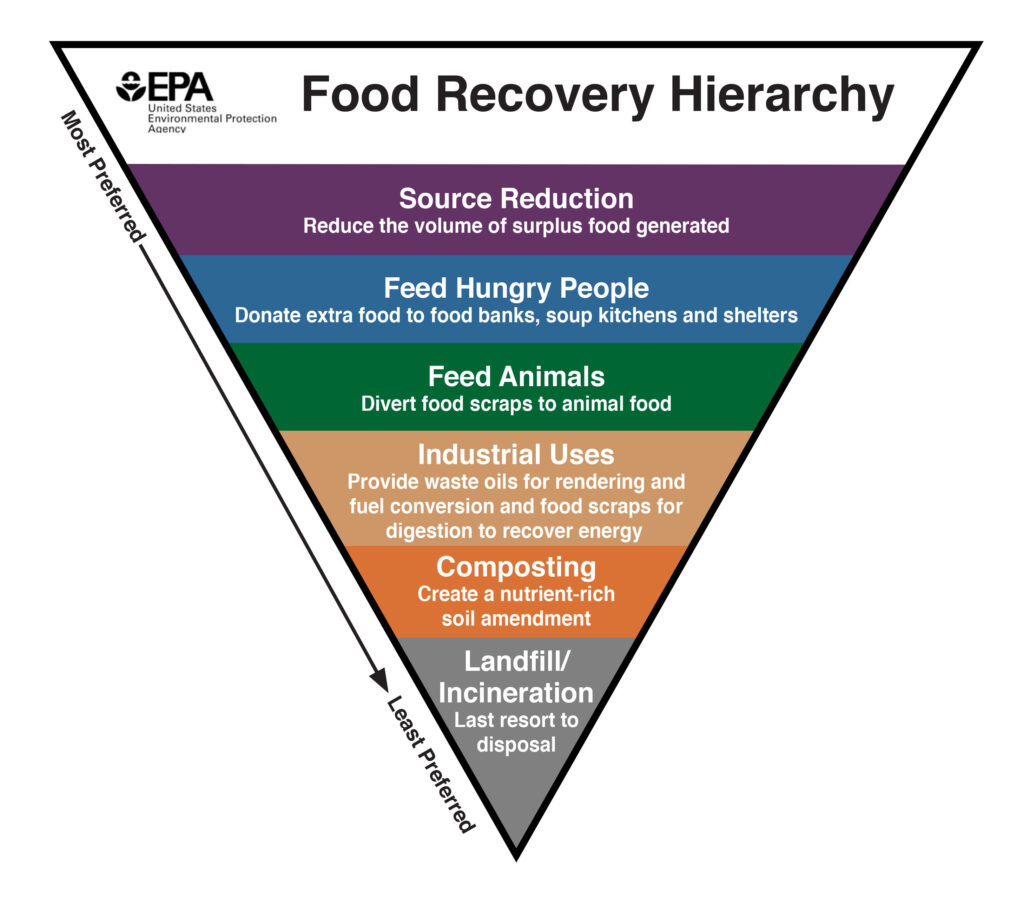

The Food Recovery Hierarchy is a model used by governments to guide what to do with food waste, ranking solutions from most to least preferred. The one on top is the Canadian one⁽⁶⁾, bottom one is from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency⁽⁷⁾. They both say basically the same thing, which is that, after reducing the amount of surplus food produced, the next best thing to do with excess food is to feed it to the people who need food.

While governments like to talk about the importance of getting surplus food to hungry people, they don’t actually do it themselves. That’s where food rescue organizations like Leftovers come in. We get the food from the donors to the service agencies, who then get the food out into the community. We’re not alone: Second Harvest, Vancouver Food Runners, Food for Life, local food banks, and many other organizations are involved in food rescue. Some food donors even have direct relationships with service agencies who come and pick up from them. We all rescue food from different places, whether that be geographic location, or large grocery chains versus smaller ones, and we all distribute it a bit differently.

But we all share the same goal: All good food gets to people who need it. No good food ends up in landfills.

It sounds great–using food that would be wasted to feed people who are hungry–but food rescue, like food banking in general, is not a solution for food insecurity. It’s not reliable enough, the food isn’t always nutritious, and it doesn’t address the whole question of dignified access. But in cities like Edmonton, which doesn’t yet have a commercial organic waste stream, food rescue does make a big difference to greenhouse gas emissions. And, just like with food banking, it means people who wouldn’t otherwise have had anything to eat today have something to eat. So until some major systemic change happens, with policies like universal basic income reducing the amount of food insecurity in our communities, food rescue organizations are still a necessary part of our food systems.

1) Tarasuk V, Li T, Fafard St-Germain AA. (2022) Household food insecurity in Canada, 2021. Toronto: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF). Retrieved from https://proof.utoronto.ca/

2) Second Harvest. (2023). Canada needs a New Year’s resolution for food insecurity. Retrieved from https://www.secondharvest.ca/resources/research/new-years-resolutions-food-insecurity

3) Gooch, M., Bucknell, D., LaPlain, D., Dent, B., Whitehead, P., Felfel, A., Nikkel, L., Maguire, M. (2019). The Avoidable Crisis of Food Waste: Technical Report; Value Chain Management International and Second Harvest; Ontario, Canada. Accessible from: https://www.secondharvest.ca/resources/research

4) Environment and Climate Change Canada. (2020). National Waste Characterization Report: The Composition of Canadian Residual Municipal Solid Waste. Retrieved from https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2020/eccc/en14/En14-405-2020-eng.pdf

5) GoodSeedVentures. (2021). Worldwide Food Consumption per Capita. Retrieved from https://goodseedventures.com/worldwide-food-consumption-per-capita-2/#:~:text=North%20America%20(USA%20%26%20Canada)%20%E2%80%93%20861.8,kg%20(2.36%20kg%20per%20day)

6) Environment and Climate Change Canada. (2019). Taking Stock: Reducing food loss and waste in Canada. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/managing-reducing-waste/food-loss-waste/taking-stock.html

7) United States Environmental Protection Agency. (2022). Food Recovery Hierarchy. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/sustainable-management-food/food-recovery-hierarchy